What’s the big deal about face? Many of my non-Asian colleagues have a hard time wrapping their heads around this question. On the flip side, when conversation turns to the topic of face with my Asian colleagues, they sigh and say, “Face issues make conflict so complicated.”

Quoting a common Chinese saying, Li Jun described face to me as an essential element in Confucian culture: “树活一张皮,人活一张脸,” which translated means: “A tree lives because of its skin; [without skin, it is naked]. It’s the same for a person: a person cannot live without face.”1 Among the Christians I interviewed in China, there was wide agreement that face often influences the start of a conflict and can keep a conflict from being resolved. So why does face have such a profound impact on conflict?

Face in the Chinese context refers to each individual’s perception or awareness of their own reputation in the eyes of others. This perception then forms the basis for their personal sense of integrity, honor, shame, prestige, and dignity.2 In Chris Flanders’ book, About Face: Rethinking Face for the 21st Century Mission, he describes face in a broader context: “Face is about the pervasive human attempt to establish a sense of worth and meaning (‘esteem’) and to find acceptance (esteem that is ‘social’).”3 Simply put, a person feels they possess face when they have the perception that their reputation is intact; they feel solid and respected in their identity; and they feel accepted and socially affirmed as having value to others and their community.

Behaviors related to conflict and reconciliation that in a Chinese context are culturally understood to cause loss of face include 1) someone critiquing or pointing out another person’s fault or mistake in the presence of a third party, and 2) personally acknowledging a mistake or being wrong. Su Lijuan explained the sensitive face challenges of having a fault pointed out when someone else is present:

If there are only two of us, I might more readily accept you pointing out my fault. But when a third party is added to the dynamic, I definitely will counterattack for the sake of my face. Even if I clearly know that what you said is right, I won’t admit it and will even strike back. You might feel baffled thinking, “I was doing this for your benefit! Why have you responded like this?” The conflict then develops. Actually, the root cause of the conflict has to do with face.4

Zhang Wei also described how, despite being Christians, face issues still make it difficult for him and his wife to admit being wrong:

Even though we both are believers, it seems that in our subconscious we can’t allow ourselves to be wrong. If I’m wrong, then there is something inside that involves face. In reality, if you’re wrong, you’re wrong; it doesn’t matter. But to be wrong, especially in front of someone you don’t know, this is a big deal. It’s not easy, and you end up burying a seed of a grudge; you set yourself up for a future problem, a storm.5

People often experience their perception of their own reputation in the eyes of others as being damaged if they admit to being wrong about something.

Socially speaking, for many in a Chinese context, preserving face at all costs is a cultural norm. Even as a Christian, the pull to preserve face is very strong for Zhou Na:

China has a saying, “死要面子活受罪” [translated as “One will go through hell for the sake of keeping up appearances” or “One will puff oneself up at one’s own cost”], meaning, for the sake of face, a person will commit a lot of sins, or bring a whole lot of trouble on oneself. Truly, sometimes I just can’t set face aside.6

With an obstacle such as this cultural norm blocking the way, reconciliation becomes nearly impossible to achieve.

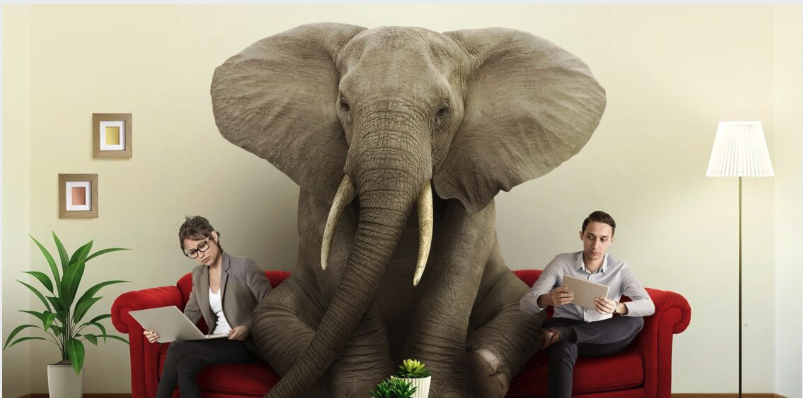

Yet God directs believers “if possible, so far as it depends on you, live peaceably with all” (Romans 12:18), so Christians must grapple with face and its impact on our relationships. There is no way around this issue. In our conflict resolution conversations, conflict coaching, and mediation help, face is sometimes the elephant in the room—if never acknowledged and addressed, reconciliation is hindered. Let’s address the elephant in the room and develop a new God-centered orientation to face.

Note: This blog post contains content from my yet to be published book, Changing Normal: A New Approach to Conflict, Face Issues, and Reconciling Relationships. Because face issues significantly impact the potential for relational reconciliation, an entire chapter of my book is dedicated to the importance of developing a theology of face, tackling questions such as: Is face bad? Should we try to get rid of face? As Christians, what should our approach to face be? How do we shift from relying on our perception of our reputation in the eyes of others to establish face to relying on the reality of our reputation in the eyes of God?

This blog post was first published on May 15, 2023 at China Source.

Image credit:Pepey via Deviant Art.

Endnotes

- Li Jun (pseudonym), author interview.

- Hui-Ching Chang and G. Richard Holt, “A Chinese Perspective on Face as Inter-Relational Concern,” in The Challenge of Facework: Cross-Cultural and Interpersonal Issues, ed. Stella Ting-Toomey (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1994), 95-132. and Chung-Ying Cheng, “The Concept of Face and Its Confucian Roots,” Journal of Chinese Philosophy 13, no. 3 (1986): 329-48.

- Christopher L. Flanders, About Face: Rethinking Face for the 21st Century Mission (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2011), 189. Chris Flanders researched face in Thai culture.

- Su Lijuan (pseudonym), author interview, location undisclosed, 2019.

- Zhang Wei (pseudonym), author interview, location undisclosed, 2019.

- Zhou Na (pseudonym), author interview, location undisclosed, 2019.